'Anatomy of Consciousness' / Moksha

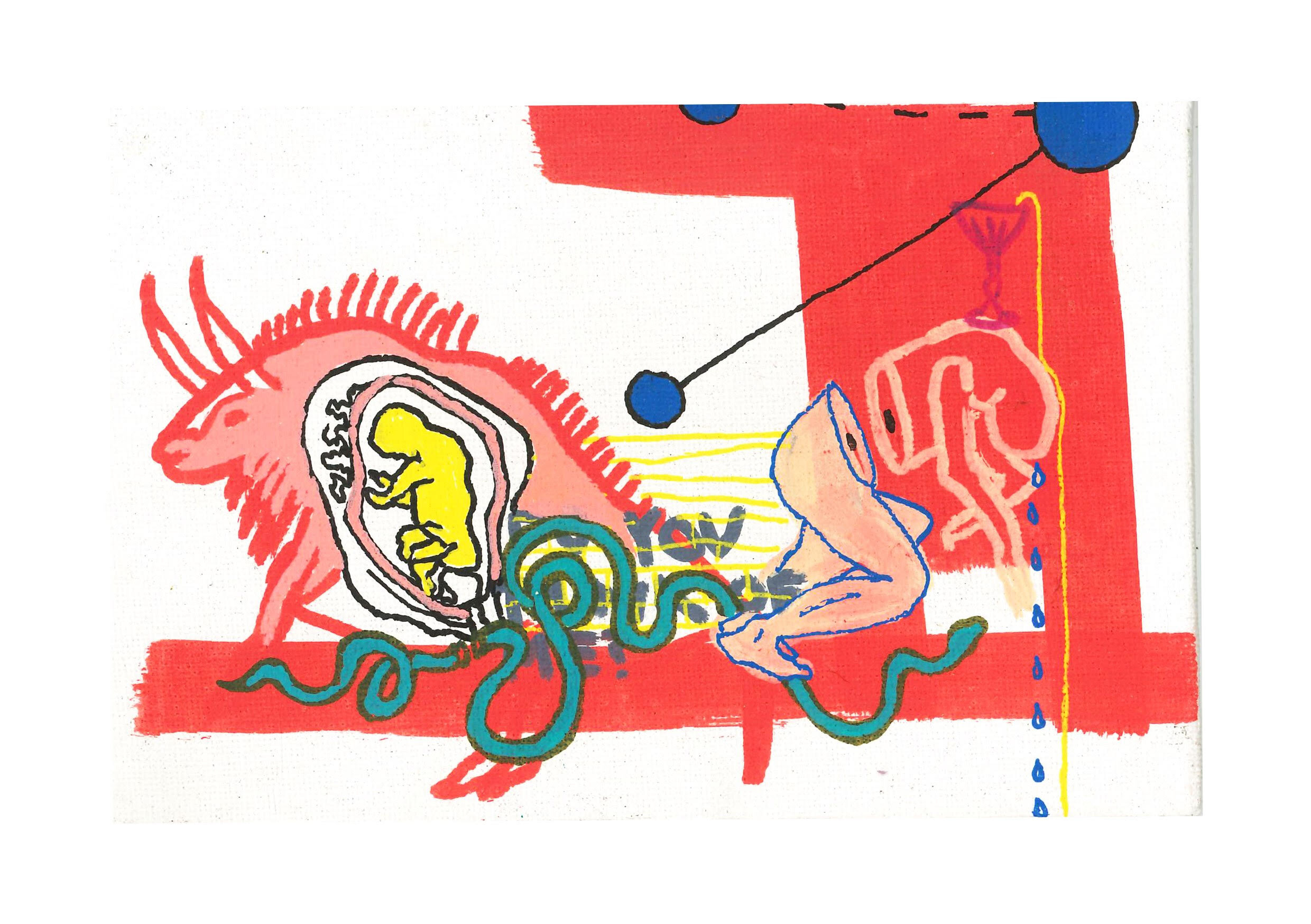

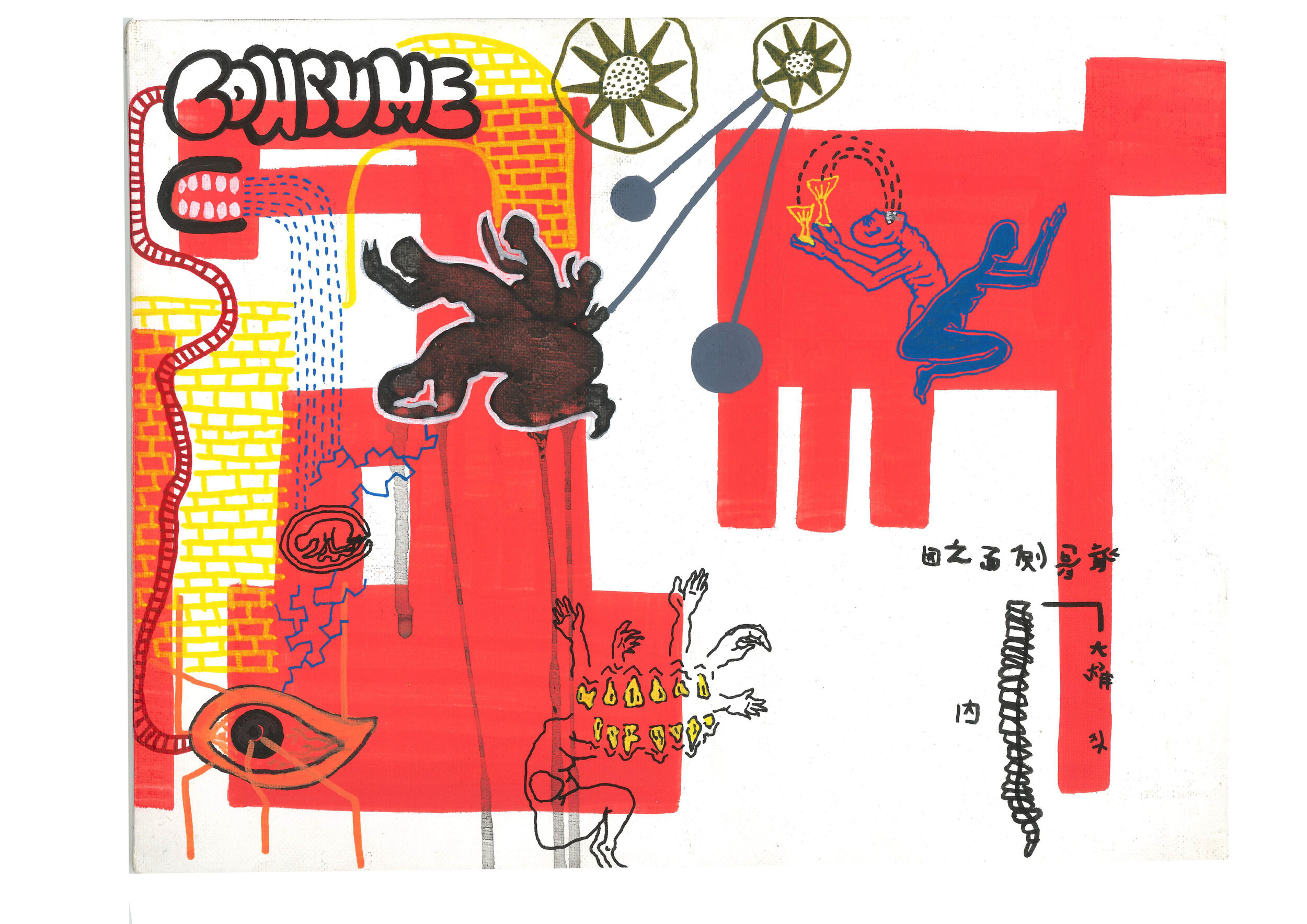

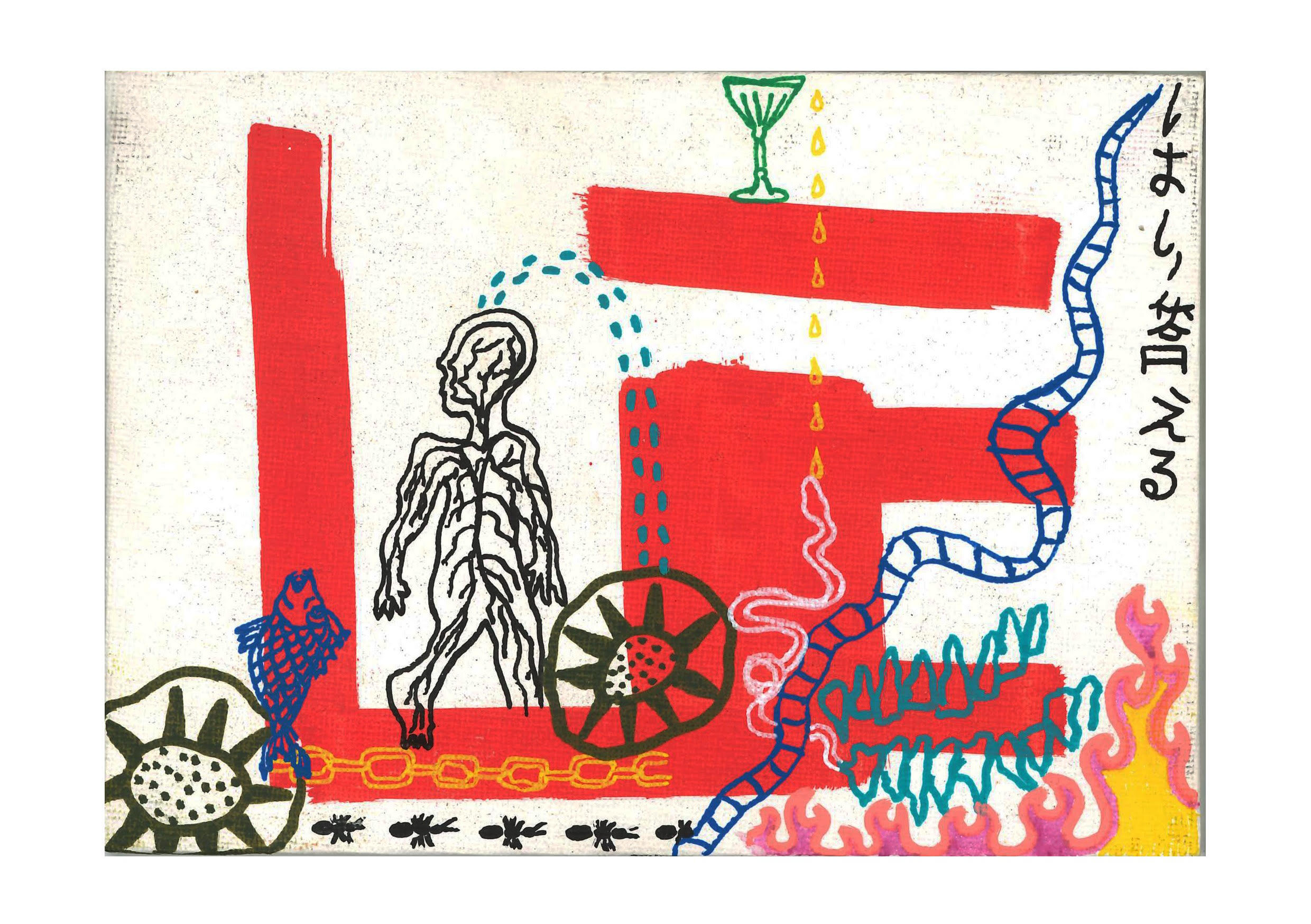

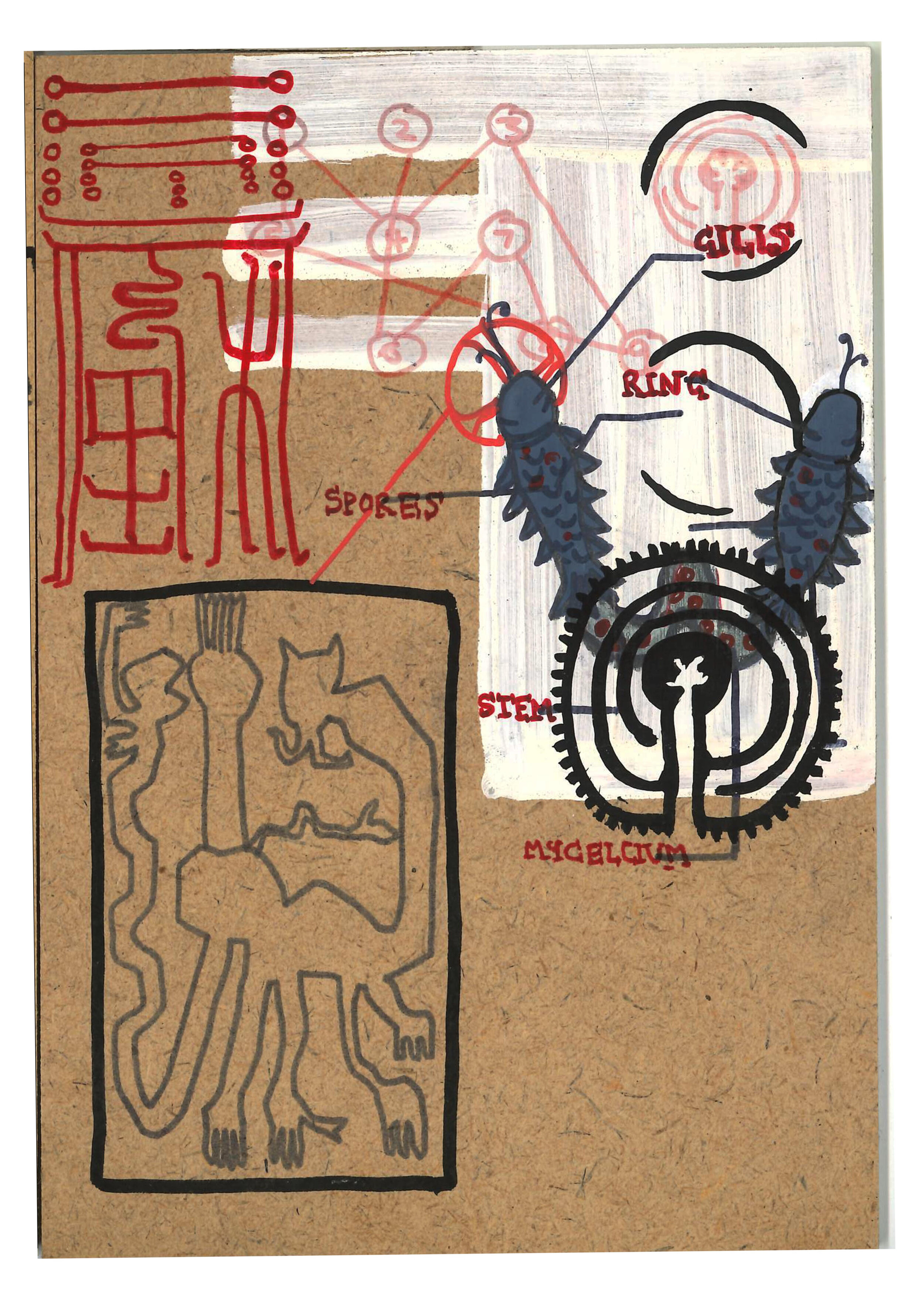

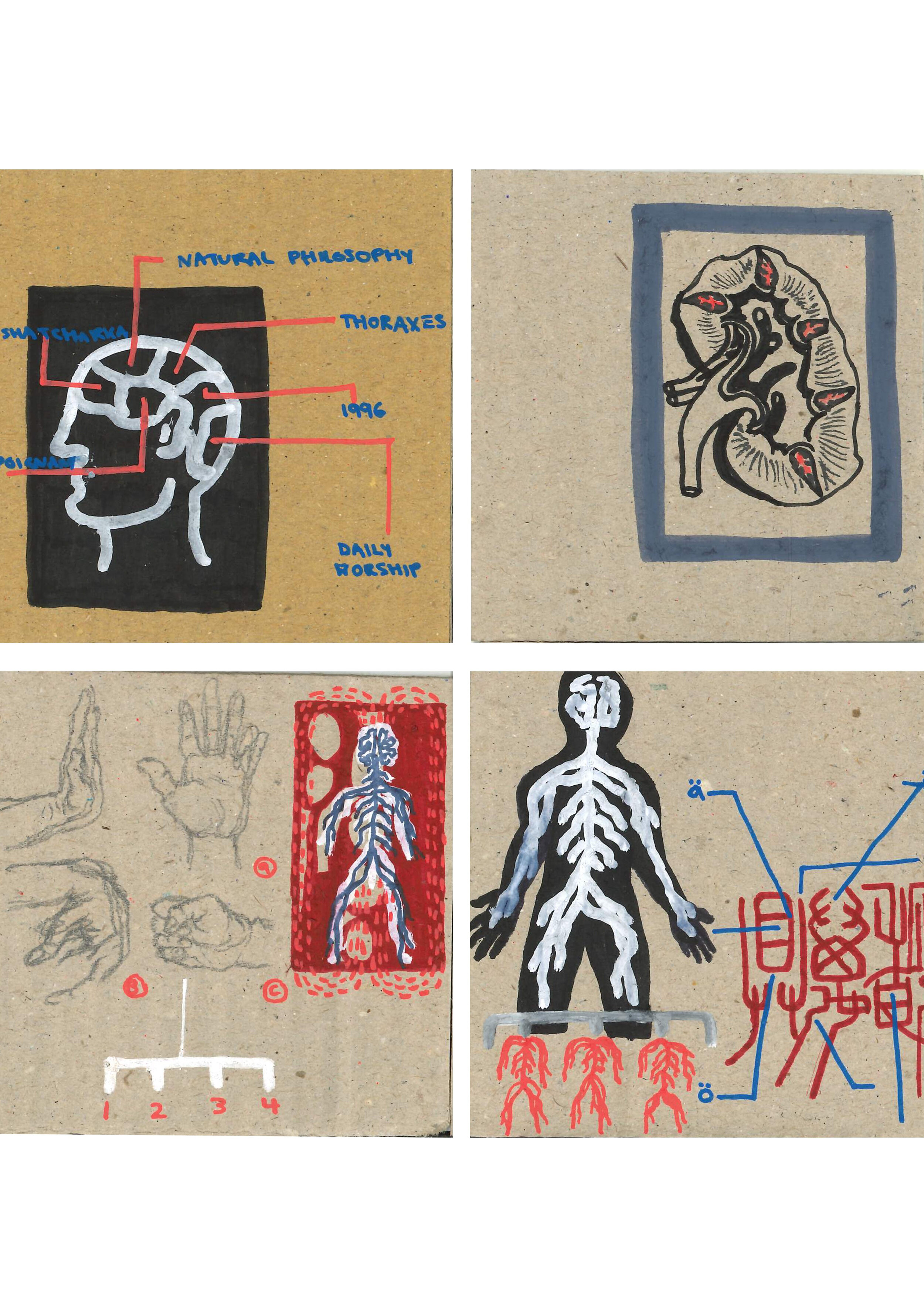

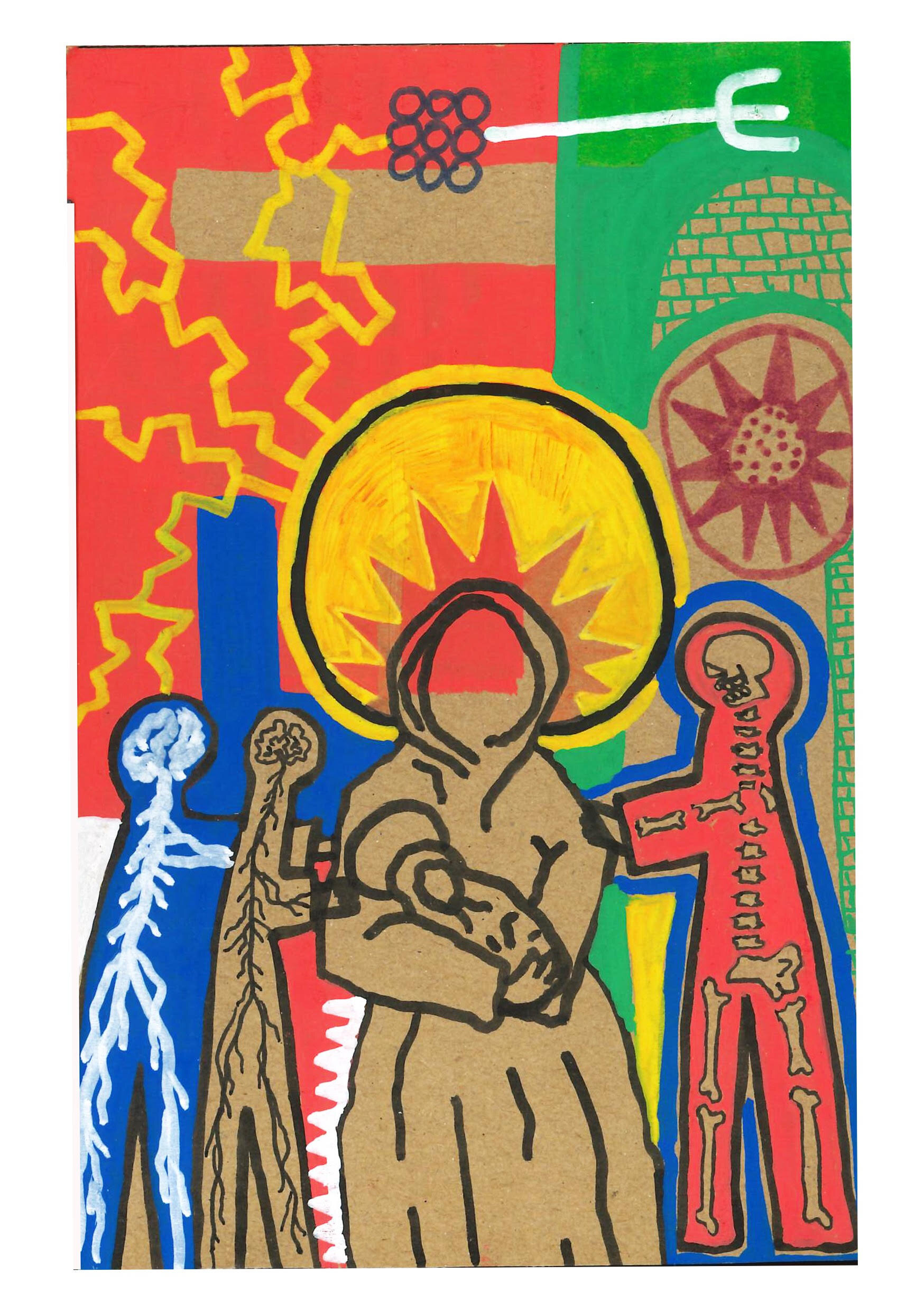

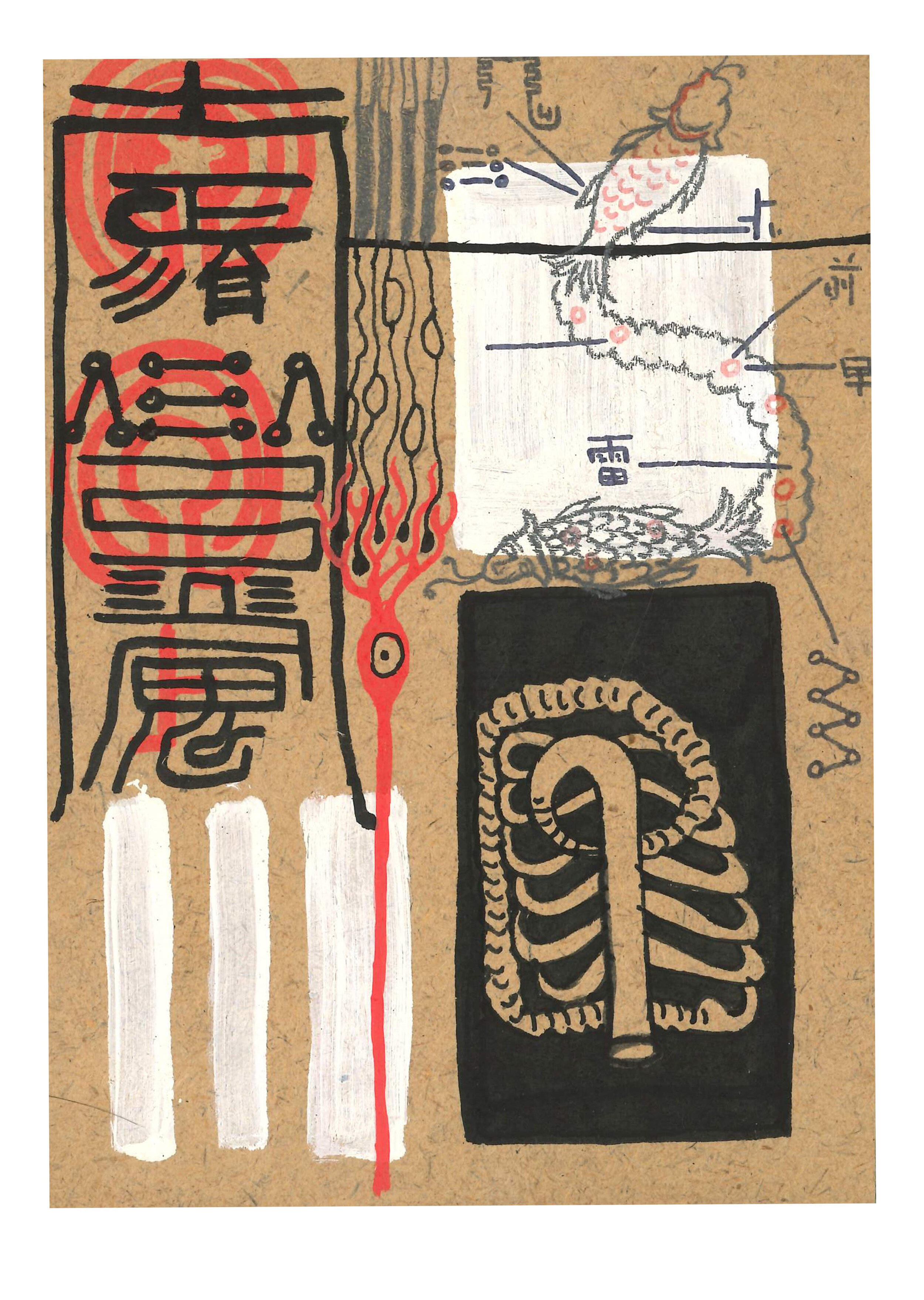

I spend a lot of time shifting through anatomical and medical journals, drawing reference from ancient historical medical manuscripts- as early in human history as I can find them. In Western medicine I draw from the works of Andres Vesalius's De Humani Corporis Fabrica, published in 1543, whose illustrations monopolized anatomical publications for over 200 years. In Eastern medical journals I draw from the ancient manuscripts of Japan’s Edo period. I am drawn to the use of primary colours, a non-typical pallet in anatomical illustrations. The beauty of primary colours arises from the fact that they cannot be mixed from other colours yet are the source of all others. Aristotle theorised that the two principal colours were black and white, followed by the two primary colours; yellow, the colour of the sun, and blue, the colour of the sky and darkness. This early observation misses only red, the colour featured most in my work.

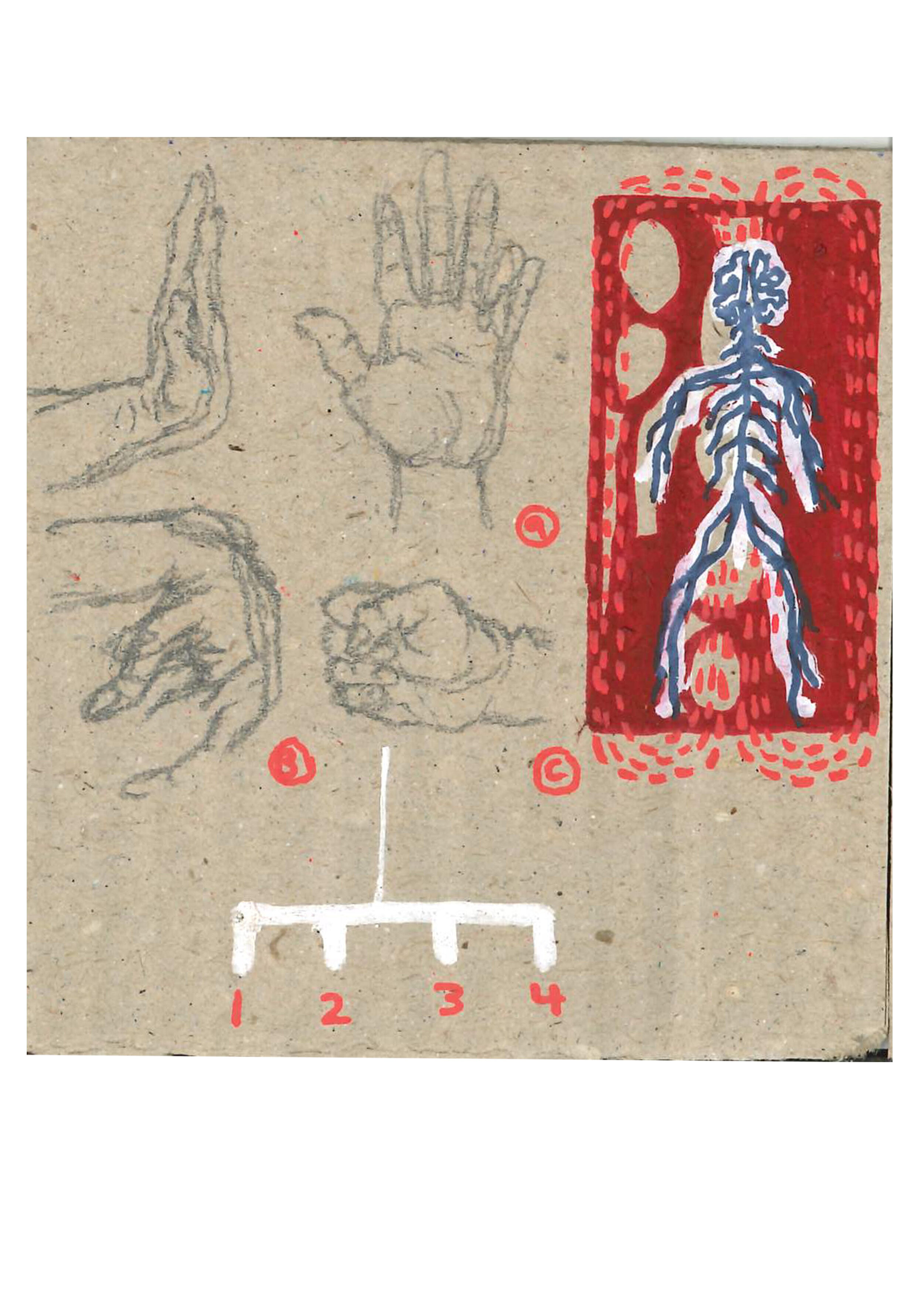

I draw the 11 human systems crudely from memory and reference the engrossing patterns found in our tissues, as seen in molecular biology. The discoveries of molecular biology however, detailed as they are, do not answer the perplexing question: where in our physical, cellular bodies does our consciousness and personality originate? My interest in this question stems back to a series I did in 2017 of 50 15cm x 15cm anatomical diagrams which conceptually sought an answer to the same question.

Consciousness has the easiest answer. Harvard students have pinpointed its physical source: a small section of our brain close to the brainstem, and two parts of the cortex which they suggest work together to give us awareness of our existence. The biological origins of personality may be more complex. The concept of neuroplasticity provides a partial answer, explaining how our brains evolve due to experience. The neural pathways which relay information between neurons, or brain cells, strengthen each time a thought, behaviour or action is repeated. Through this process the structure and function of the brain is altered at multiple scales- from the microscopic changes of individual neurons to larger-scale changes such as the restructuring of neural networks (groups of connected brain cells) in response to injury. Although these explanations still leave a lot of questions unanswered, the real insight I have gained from my research is the understanding that the mind can be remapped, new pathways strengthened and intrinsic behaviour changed. For those struggling with mental health issues, this is promising knowledge.

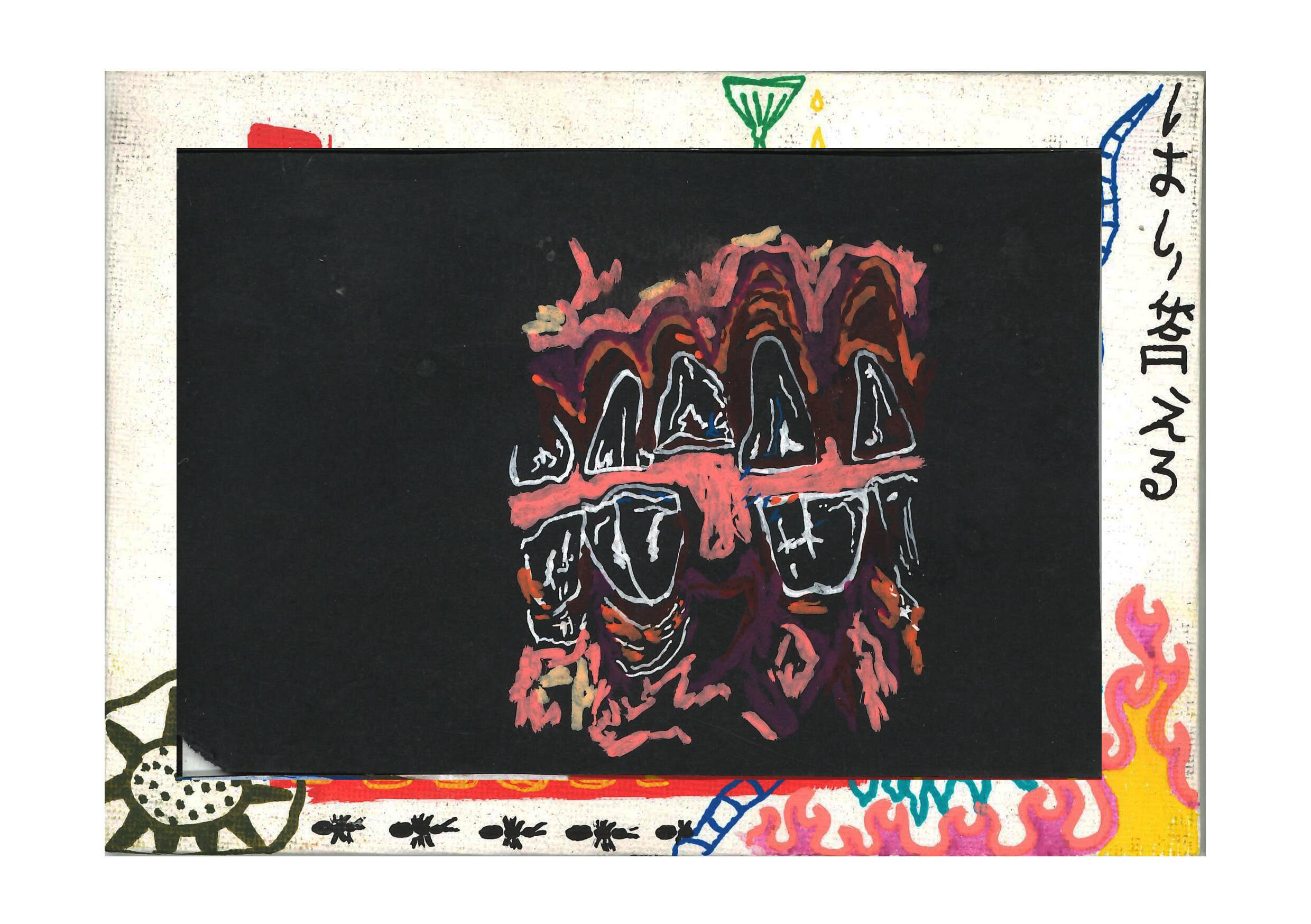

In my own practice I have the opportunity to merge historical, religious, and contemporary understandings from both the East and West along with my own experience of consciousness. I am able to use reoccurring symbols from within the body as motifs of the expression of my emotional state. Two of the most reiterated of these is the nervous system (anxiety, discomfort) and a child in a womb (sadness, longing for security and depressive state). On a more trivial and obvious scale I see my art reflect my experiences on a daily basis: wisdom teeth pain translates into short obsession with drawing teeth, and intellectual experiences translate into a fascination with representing brain structure and neurons.

Art, unlike science, has the ability to express the surreal and the emotional experience of consciousness. Illustrations formed within and made for the scientific community are often bound to the explicable, to their roles in education and to precision and accuracy. The repurposing of anatomical images in art, however, is not bound by these constraints. It allows for an unrestrained exploration of historical understandings about the origins of our conscious selves, their relation to current beliefs, and the complex nature of humanity’s search for self-understanding.

Contact Moksha via Instagram: @_mummys_boy_